A MERICANS USED TO recoil at secret diplomacy as an affront to democracy. Back-channel intrigues thwarted accountability, concentrated power in the presidency and bred mistrust. In 1918 Woodrow Wilson piously announced that he sought “open covenants of peace, openly arrived at”. Yet Wilson himself found it expedient to use a close political adviser, Edward House, as a back channel to foreign leaders. “Colonel House”, as his Texan factotum was known, was given quarters in the White House and became Wilson’s chief negotiator in Europe to end the first world war.

Successive presidents have found at least three sensible reasons for secret diplomacy. The first is to rely on an especially trustworthy aide, like House. Harry Hopkins, a shrewd adviser to Franklin Delano Roosevelt, functioned as almost a one-man State Department—eclipsing the actual secretary of state, Cordell Hull. Hopkins, like House, was so close to his boss that in 1940 he moved into the White House. Roosevelt once told another politician “what a lonely job this is, and you’ll discover the need for somebody like Harry Hopkins who asks for nothing except to serve you.”

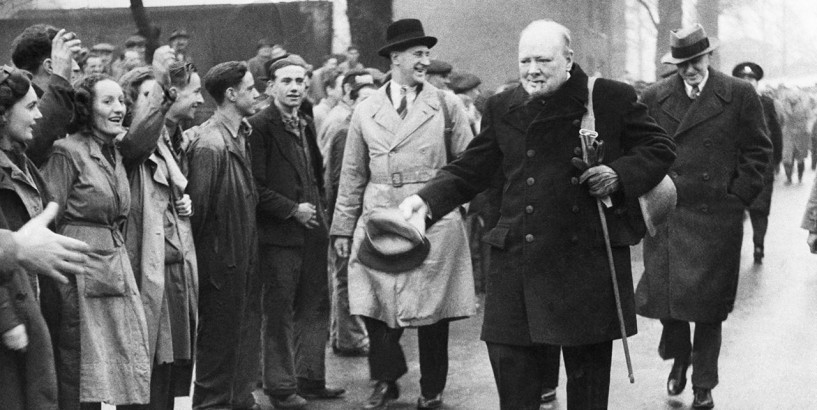

During the second world war, Roosevelt put Hopkins in charge of the Lend-Lease aid programme. In January 1941 he sent him, frail from stomach cancer, to London, in the Blitz, to establish a direct connection to reassure Winston Churchill. Hopkins was amused by the “rotund” and “red faced” prime minister, reporting to Roosevelt that “the people here are amazing from Churchill down and if courage alone can win—the result will be inevitable. But they need our help desperately.”

Soon after Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, Hopkins undertook a harrowing trip to see Josef Stalin. In Moscow, blacked-out to withstand German air raids, his hosts provided him with a bomb shelter equipped with caviar and champagne. At the Kremlin, Stalin admitted to Hopkins that it would be hard for the Russians and British to win without the Americans joining the fight. Chilled by Soviet tyranny, Hopkins was nevertheless impressed by the resolute “dictator of Russia”: “an austere, rugged, determined figure in boots that shone like mirrors”, whose “huge” hands were “as hard as his mind”.

John Kennedy, too, found it helpful to reach out to the Russians through his most trusted man: his brother Robert Kennedy, appointed attorney-general in an act of breathtaking nepotism. Although foreign policy was well outside his brief at the Justice Department, Robert cultivated the Soviet ambassador, Anatoly Dobrynin, and befriended Georgi Bolshakov, a military-intelligence officer. Early in the Cuban-missile crisis, Nikita Khrushchev ordered Bolshakov to tell his American friend that the Russians were placing only defensive weapons in Cuba—an obvious lie.

Yet the back channel worked when it mattered most. At the height of the crisis, on October 27th 1962, the president got his brother to invite Dobrynin to his office at the Justice Department. If the Russians would disable their missile sites in Cuba, Robert Kennedy said, there would be no invasion of Cuba. When, as expected, Dobrynin asked about withdrawing Jupiter missiles from Turkey, he confidentially replied that the president saw no “insurmountable difficulties”, insisting only that the swap should be done a few months later and kept secret. This would become part of the deal that brought the superpowers back from the brink of nuclear war.

A second standard use of a back channel is to hold exploratory talks that could easily blow up. If there is to be egg on someone’s face, it should not be the president’s.

Barack Obama’s administration did this in the early stages of its nuclear deal with Iran, using a back channel in Oman starting in 2011. When the Omanis suggested a discreet meeting between American and Iranian officials in Muscat, the Obama administration gingerly chose an exploratory meeting with a lower-level delegation, led by Jake Sullivan, an aide to Hillary Clinton, the secretary of state. “We had been burned so many times in the past few decades that caution seemed wise,” writes William Burns, the former deputy secretary of state, in his book “The Back Channel”.

In February 2013 Mr Burns led an American delegation to a second meeting in Oman—the first of many 17-hour flights to Muscat in unmarked planes with blank passenger manifests. The secrecy, Mr Burns writes, was meant to keep opponents of a nuclear deal in both Washington and Tehran from scuppering the initiative at the outset. Mr Obama once told Mr Burns, “Let’s just hope we can keep it quiet, and keep it going.”

A third reason for shadow diplomacy—which often overlaps with the second one—is to start talking with a reviled enemy state. In such cases the White House will face blowback from opponents at home and allies abroad. The prime example is Richard Nixon’s opening to China.

The Nixon administration tried numerous clandestine channels to Mao Zedong’s regime, including through Charles de Gaulle in France, the communist tyrant Nicolae Ceausescu in Romania and the military dictator Agha Muhammad Yahya Khan in Pakistan. Mao sent back almost identical invitations through the Romanian and Pakistani channels for an American special envoy to visit Beijing. Henry Kissinger, then Nixon’s national security adviser, coveted the historic first trip to Beijing for himself. When Nixon suggested sending the elder George Bush, the American ambassador to the United Nations, Mr Kissinger cut him dead: “Absolutely not, he is too soft and not sophisticated enough.”

A stomach for subterfuge In July 1971 Mr Kissinger secretly flew from Rawalpindi to Beijing, explaining away his 49-hour absence with a cover story that he was recovering from a sick stomach at a Pakistani hill resort. His mission paved the way for Nixon’s own visit in February 1972.

There was a terrible human price for the Pakistani channel. Pakistan’s dictatorship was slaughtering its Bengalis in one of the worst atrocities of the cold war. Before Mr Kissinger’s first trip to China the CIA and State Department secretly estimated that some 200,000 people had died. “The cloak-and-dagger exercise in Pakistan arranging the trip was fascinating,” Mr Kissinger told the White House staff when he returned to Washington. “Yahya hasn’t had such fun since the last Hindu massacre!”

Bill Clinton faced a similar problem while brokering an end to the war in Bosnia. After the Bosnian Serb leaders Radovan Karadzic and Ratko Mladic were indicted by a UN war-crimes tribunal in July 1995, the Clinton administration kept them at arm’s length. Yet it maintained several secret channels to them: through a European Union envoy, the UN force commander in Bosnia and Russia’s deputy foreign minister. Mr Karadzic also flaunted his relationship with Jimmy Carter, a former American president turned mediator.

In September 1995, while NATO was bombing Bosnian Serb forces, Richard Holbrooke, Mr Clinton’s hard-charging peacemaker, met Slobodan Milosevic, Serbia’s president, at a hunting lodge outside Belgrade. The Clinton administration preferred to work with Milosevic, who had not yet been indicted for war crimes. Yet Milosevic told Holbrooke that Messrs Karadzic and Mladic were at another villa 200 metres away. Holbrooke despised the fugitives but had grimly made up his mind to meet them. In exchange for a halt to NATO ’s bombing, the Bosnian Serbs grudgingly agreed to lift their siege of Sarajevo. In the formal peace talks that followed at Dayton, the Americans excluded Messrs Mladic and Karadzic and dealt mainly with Milosevic.

There is a darker reason for circumventing normal foreign-policy channels: to break the law. Some of the examples here are less about secret diplomacy than covert action, but they are chilling.

In December 1971, when Pakistan attacked India, Nixon and Mr Kissinger used back channels while illegally helping Pakistan with American military supplies—particularly American-made warplanes sent from Iran and Jordan. Pentagon and State Department lawyers and White House staffers warned that this would violate a formal American arms embargo on Pakistan. As Mr Kissinger told Nixon, “It’s not legal, strictly speaking, the only way we can do it is to tell the shah [of Iran] to go ahead through a back channel.” A few days later Mr Kissinger told the president that they would get an envoy secretly to “get the god-damned planes in there.”

The national interest, or mine? Perhaps the closest precedent to President Donald Trump’s pressure on Ukraine to investigate the front-runner in the Democratic primary comes from Nixon’s presidential campaign in 1968. That year Nixon, as the Republican nominee, set up a personal channel to the South Vietnamese government. Nixon could pass messages to South Vietnam through Anna Chennault, a well-connected Republican fundraiser. A few months later Nixon’s campaign got word that Lyndon Johnson’s administration might be about to declare a halt to its bombing in Vietnam to spur peace talks—a thunderclap that might have won the presidency for his faltering Democratic rival, Hubert Humphrey, Johnson’s vice-president. Just before the election, that sort of deal seemed imminent—but then South Vietnam suddenly backed out.

Johnson was convinced that Nixon’s campaign had been involved. “Keep Anna Chennault working on SVN [South Vietnam],” Nixon had ordered H.R. Haldeman, his future White House chief of staff, according to Haldeman’s notes. The FBI , which was wiretapping the South Vietnamese embassy, told Johnson that Chennault had passed on a message from “her boss”, which was: “Hold on. We are gonna win.” Johnson raged privately: “This is treason.” More accurately, such actions would probably have been a crime under the Logan Act, which bans private American citizens from interaction with foreign governments “to defeat the measures of the United States”.

What would George Washington do? Historians have not been as sure as Johnson about Nixon’s guilt, but two recent biographies, by Evan Thomas and John Farrell, both conclude, with varying degrees of certainty, that Nixon worked to hold South Vietnam back from peace talks that might have helped Humphrey. In hindsight, it is not clear how much of an opportunity was lost to end the war, but Nixon could not have known that when he gambled with Vietnamese and American lives.

On Ukraine, Mr Trump went to great lengths to circumvent his own White House and State Department, where professionals might recoil at pressuring a foreign government to dig up dirt on a domestic rival. Rudy Giuliani is not a government official but his personal lawyer. In his telephone call to Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, on July 25th Mr Trump said, “I will have Mr Giuliani give you a call.”

Unlike previous presidents, Mr Trump had no proper reason here to operate in the shadows. His administration was dealing not with a pariah such as Mr Karadzic, but with an elected democratic leader. Mr Giuliani is no Harry Hopkins, Henry Kissinger or Richard Holbrooke. Hopkins, Holbrooke and others may have worked in secret, but they were carrying out official policy that was meant to serve American national purposes, not personal or political goals. If there is any historical precedent for Mr Trump’s Ukraine channel (other than his own campaign’s dealings with Russia in 2016), it is that of Nixon stalling peace talks in Vietnam for his own political good. Yet Nixon in 1968 was only a candidate; Mr Trump was exploiting his power as president, able to hold up a summit with Mr Zelensky and to withhold $391m in military aid that had been authorised by Congress.

Marie Yovanovitch, a former ambassador to Kiev, testified to Congress that “unofficial back channels” between the White House and corrupt Ukrainians led to her removal by Mr Trump. This points to another difference. Back channels have in the past been used by presidents as a way to bring American influence to bear on the world. This one worked in the opposite direction. Mr Giuliani’s scheme gave people working against American policy a line from Kiev into the Oval Office.

The White House will always be tempted by the shadows. Presidents rather more scrupulous than the current one have been lured into secret diplomacy and dodgy covert operations, from the Bay of Pigs to the Iran-contra scandal. Enough secret misbehaviour has already gone on in foreign policy. If Mr Trump is permitted to use back channels abroad to target political rivals at home, that will set a terrible precedent. ■