It is not often that academics become household names - still less that their works come to define an era.

But that was precisely what happened 30 years ago when a little-known political scientist called Francis Fukuyama came to prominence in remarkable fashion.

It was the year the Berlin Wall fell and the Iron Curtain was lifted across eastern Europe, the year the fall of the Soviet Union became an inevitability and the Cold War seemed to be at an end.

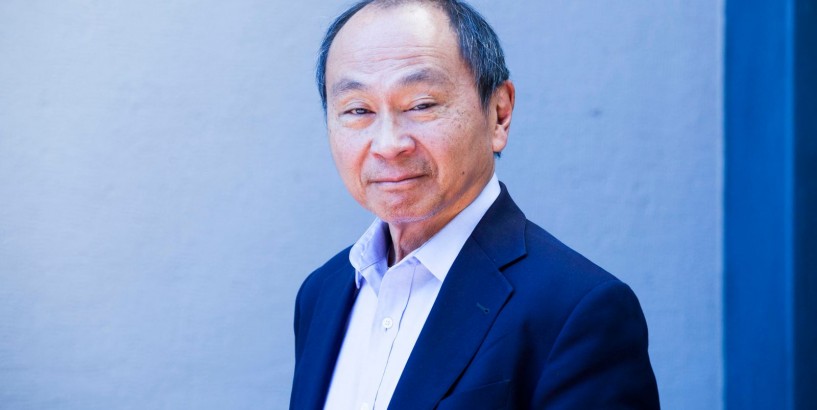

Image: Fukuyama believes Brexit makes Britain a less powerful country And few pieces of writing seemed to encapsulate the significance of the moment more than Fukuyama's paper, published in the summer of 1989 - The End Of History?

Most of post-war history had, one way or another, focused on the clash between democracy and liberalism on the one side and communism on the other.

Advertisement Throughout that period, as the Cold War raged and fingers hovered near nuclear buttons, there was another question that dominated political science: was Marx right? Was capitalism really just a phase on the inevitable road towards communism? Did history have one more chapter in store for everyone?

No, wrote Fukuyama in the article. He said: "What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of postwar history, but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind's ideological evolution and the universalisation of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government."

More from World Australia wildfires: Two dead and hundreds of koalas killed as blazes rage across east coast Syria: Death of Kurd in protest against Turkish 'invaders' is 'significant moment' How the Berlin Wall split the world until 30 years ago The Berlin Wall may have gone but East-West tensions are as potent as ever Roman Polanski accused of 'violently raping' French teenage actress KSI v Logan Paul: KSI clarifies after telling Logan Paul he's 'going to f die' It was a striking thesis. Even though the paper's title ended with a question mark, even though it was prefaced with provisos and Fukuyama reinforced that doubt a couple of years later by turning the paper into a far longer, more nuanced tome called The End Of History and the Last Man, the force of his thesis was too powerful to resist.

As the walls fell and the Soviet Union crumbled, the conventional wisdom snowballed: maybe Fukuyama was right. Maybe this was indeed the end of history and what he called "the triumph of the West".

Thirty years on and one could spin a very different narrative. What if 1989 was not the end of history but the beginning of a whole new chapter?

Communism may have been vanquished in most of the world, democracy may be far more widespread but political instability is at a greater reach than ever before.

Anti-establishment politics is on the rise everywhere: you can see it in Brexit, in the election of Donald Trump and in nearly every developed economy.

Image: Anti-establishment politics is on the rise everywhere, with the election of Donald Trump as an example Enthusiasm about liberalism and democracy is on the wane. The Soviet Union has collapsed but Vladimir Putin seems intent on reassembling something like it.

And while China may have embraced market norms it is hardly any more democratic than it was three decades ago. What, in other words, if Fukuyama got it completely wrong?

When I put this question to Fukuyama in a Sky News interview to commemorate the 30 years that have passed since, he took one of those intakes of breath that suggested he is a little tired of being asked the same thing over and over again.

After all, in the intervening years he has written a series of considered, sophisticated works on politics, statecraft and history, yet it is this article which continually comes back to haunt him.

"The basic argument was, I think, fundamentally misunderstood," he says. "The end of history didn't mean that democracy would triumph everywhere and always. In fact, I said nationalism and religion are going to continue to be powerful forces.

"For 150 years the Marxists had said that the end of history is going to be communism - that that's the highest form of society. And in 1989 I just made a simple observation: it didn't look like we're going to get there. We were going to stop at the stage before communism, which was liberal democracy tied to a market economy.

"The real question I was trying to ask was: is there actually a better alternative out there? Because I didn't see one then. And, quite frankly, I don't see one now."

Indeed, since the 1970s the number of democracies around the world has risen from around 30 to more than 110. But the nature of those democracies is hardly as straightforward as many assumed 30 years ago.

Is Russia a democracy or something else? Fukuyama calls it and China "consolidated authoritarian regimes". Though when he thinks of worrying patterns across the democratic world he finds himself even more concerned with what's happening in the US and Britain.

"You've had the rise of populist movements that I think are threatening democracy from within," he says.

Image: Fukuyama with former Soviet Union President Mikhail Gorbachev during a conference in Moscow in 2007 "They're threatening the constitutional checks and balances that are really part of a functioning liberal democracy. And it's spreading to other parts of Europe. Hungary and Poland both have populist governments. Italy had one for a bit, [so does] Brazil.

Further afield in India you've got [Prime Minister Narendra] Modi, who is trying to shift India from a liberal constitution to one based on Hinduism, which I think promises a lot of conflict, both social and international in the future. So it's a very difficult moment for global democracy."

And contrary to what people sometimes assume, Fukuyama says he does not believe democracy is inevitable. One gets the impression this is in part down to cold, hard experience.

In 1989 he wrote hopefully of tens of thousands of Chinese students studying in the US and Europe: "It is hard to believe that when they return home to run the country they will be content for China to be the only country in Asia unaffected by the larger democratising trend."

Yet today the country may be comfortably the world's second biggest economy but it is, if anything, even more authoritarian under president Xi Jinping (educated not in the US but in Beijing's Tsinghua University). How does Fukuyama square this with his beliefs?

"As you get richer, you've got a middle class and the middle class has different preferences - they want more participation, they have property that they want to protect. And so the argument was that a country like China, as it got richer, would move towards democracy.

Image: China may be even more authoritarian under president Xi Jinping "And that is not right. Unfortunately, that's a theory that's currently being disproved because China is far richer than it was 10 years ago. Yet that middle class does not seem to be bucking this trend towards ever-tighter authoritarianism.

"The question is whether any of these alternative forms are actually going to be more sustainable and more successful [than democracy] in the long-run. And that, I think, has yet to be proven.

"I think the Chinese system has got a lot of weaknesses; for instance they've never really had to deal with a big recession or economic setback. Whether that regime can maintain its legitimacy if that were to happen, we don't know."

Still, the tone has certainly changed since 1989 and a lot of that is down to the imperceptible shifts that happened beneath the surface in the intervening period. For 1989 wasn't just a political story but also an economic one.

Suddenly liberal western democracies and the international organisations that underpinned them - the UN, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and World Trade Organisation - had no competition.

It's worth remembering that for much of its existence the UN Security Council was effectively toothless since the Soviet Union or China could easily veto any resolution brought to it by western democracies.

Suddenly in the early 1990s that changed. Security Council unanimity became a possibility. It is no coincidence that the Iraq War followed shortly afterwards.

There was also a broader economic shift. Now that communism and full-blooded socialism had been discredited an emboldened West pushed even more aggressively for the kinds of liberal reforms that, they felt, had worked so well back home.

The World Bank and IMF pursued what came to be known as the "Washington consensus": imposing market-friendly reforms on emerging economies. Those reforms and that advice felt right in Washington, it seemed in tune with the economic rules they were taught at college, but when those policies were imposed on fragile, poor economies they sometimes led to catastrophe.

Image: Fukuyama calls Russia and China 'consolidated authoritarian regimes' Across a host of economies, from Argentina to Asia, there were a series of financial crises which were, if anything, worsened and deepened by that economic advice rather than improved by it.

In rich countries those market friendly reforms were imposed by both right wing governments but also by centre left leaders like Tony Blair and Bill Clinton. Over the period inequality rose sharply.

But because this was the end of history there was no plausible alternative. Whereas for much of the 20th century there was a constant battle of ideas between the Soviets and the United States, at the turn of the millennium there was only one game in town: the Washington consensus, or, as some call it, neoliberalism.

"It was a form of market fundamentalism: governments were bad, they had to get out of the way." says Fukuyama. "The policies that came out of that resulted in the globalised world that we live in today. It has produced an incredible amount of wealth: global GDP increased by a factor of four between 1970 and 2008.

"But it also created a lot of inequality. A lot of oligarchs emerged, not just in Russia and Ukraine, but all over the world. There were concentrations of wealth. And I think that is at least part of the economic background for the current backlash, because that globalisation didn't really lift all boats as promised."

Equally important, adds Fukuyama, was the cultural reaction that came alongside that economic shift.

"What happened as a result of this growing inequality was a cultural cleavage that emerged between people that had good educations, opportunities, were mobile and could take advantage of this new cosmopolitan world that was opening up and people that were more traditional, fixed and conservative in their social values.

Image: Francis Fukuyama pictured in Paris in 2002 "That's the cleavage that runs through many countries that have experienced populism. It really has to do with respect and dignity.

"If you listen to the language of populist voters, a very important theme is that 'the elites that are ordering our world despise us - they look down on us' or, at best, 'we're invisible to them: they don't care about our lives and the way that their policies, like immigration, high levels of immigration, have affected my village or my community'.

"And I think that lack of feeling of respect is really what creates the anger that then drives the populist vote in many places."

That anger has contributed to the rise of powerful forces on the left as well as the right. In the UK Jeremy Corbyn is proposing nationalising railways and utilities and raising the top rate of tax significantly.

In the US one of the most prominent candidates for the Democratic presidential nomination, Elizabeth Warren, has proposed breaking up the tech giants and imposing a wealth tax on the richest Americans. Do those kinds of policies scare Fukuyama?

"Elizabeth Warren wants to apply antitrust laws to tech companies. And to tax more. And I think actually both of those things are things that I would support."

Mr Corbyn, on the other hand, may call himself a socialist but his brand of socialism is not exactly a return to the pre-1989 era, says Fukuyama.

"I don't actually think it's a return of socialism. Socialism really is associated with an authoritarian government that nationalises the means of production. This is really more an overdue shift towards more social democratic policies. I don't particularly like Jeremy Corbyn's policy preferences, but I don't think he's going to abolish democracy."

Image: Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn isn't a true socialist in Fukuyama's eyes What, though, does this internationally-renowned professor of political science think about Brexit? Is it a downgrade of Britain's prospects or an opportunity for the UK to break free of its European bonds and forge a new identity on the global stage?

"I don't really see how it can be other than a diminution of the standing," he says. "Just within the United Kingdom itself, Brexit is going to unleash a lot of tensions with Ireland and with Scotland. But it also does seem to be a rejection of the kind of intense leadership role that Britain has played.

"And part of that was actually about being part of the European Union. [The UK] was the voice in the EU for a more market-oriented, less state [focused] set of policies.

"And that's being given up. Internationally, it's not something that's conducive to a strong leadership role in restructuring the international system in terms of economics or security or anything else. So I do think it is a choice for a less powerful country."

Still, in case you were under the impression that what with the rise of populism and the stickiness of authoritarianism, Fukuyama is downbeat about the future of the world, don't be fooled.

"I do think that there are reasons not to panic at the present moment," he says. "We are going through a really rough patch and this is why political agency - the idea that leaders matter and public who vote certain ways matter - will determine the future.

"But there's no mechanism like the Marxists used to believe in that inevitably pushes us in a certain direction."