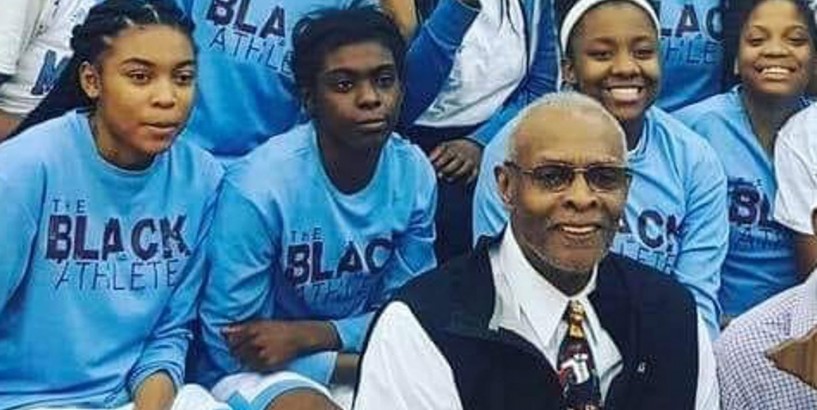

Larry Moore talked to his best friend on the phone two weeks ago. He sounded fine. On Sunday night, Moore got a call that Dwight Jones was gone. It was the novel coronavirus. It happened that fast. “I’m in shock,” said Moore, speaking about the man he considered his brother, about the man who coached and taught at Detroit's Mumford High School for nearly 50 years. Too many of us are getting the phone calls that Moore got Sunday night. And we’re not sure where to put the grief. Or how to process it. Jones and Moore coached boys and girls basketball together at Mumford High School. And while Moore was just a year younger — Jones was 73 — he looked up to the long-time educator. So did hundreds and hundreds of players and students. Moore has taken calls non-stop from those players and students the past couple of days who wanted to talk about what Jones meant to them. Others took to social media to express condolences and share stories. Under normal circumstances, a teacher and coach like Jones would be memorialized within a week or two, and those who loved him would gather and grieve. “And send him off,” said Moore. But now? “It's impossible,” said Moore. “You can’t get together.” Can’t cry together. Can’t pray together. Can’t laugh together. Can’t reminisce together. Can’t pay respects together. “These are difficult times,” said Moore. “As for the families? I can’t even imagine.” Jones was the kind of person who will draw 1,000 people to a service. He changed that many lives — the school recently named one of its gyms after him. But a service will have to wait. Which means the grieving process will have to wait. Because coming together after a death is essential to navigating grief. Thousands of families around the country are navigating death in this new reality, as a critical step in their grief has been put on hold. What will take its place? Staying connected on the phone and online. Word spread quickly Sunday after Jones’ death. Darren Nichols learned about it on Facebook, where he in turn spread the news with a remembrance. Nichols played for Jones and Moore in the mid- to late '80s, first on the junior varsity team, then on the varsity team. “He was tough,” said Nichols. “He was a disciplinarian. And he had to do things his way.” He also was honest, straightforward and pushed his players and students relentlessly. “He loved one-liners,” said Nichols. He once told Nichols that he was slower than Christmas. And Nichols was. And he worked on it. And increased his speed and quickness. “He genuinely cared about you,” said Nichols, who developed a friendship with Jones, traveling to the Final Four with him and other area coaches every year. “We used to sit in the lobby and talk about everything.” Jones loved being around the coaching clinics before the games in each Final Four city, but he also liked the vendor shows. He was always searching for a good deal on uniforms and equipment — he served as the school’s athletic director for a time, too. “He wasn’t afraid to use his own money to help, either,” said Steve Fishman, a criminal attorney who played basketball at Mumford in the '60s with Moore and who developed a friendship with Jones over the years. “How many people do that? On a teacher’s salary?” Jones helped his players get scholarships to college and sent several students to Tennessee State, where he played basketball on a scholarship. He excelled as a coach and teacher. Not just by winning, but by sticking with kids beyond the gym and beyond graduation. In his mind, that started with honesty and bluntness. He didn't mind telling players they couldn’t shoot, or dribble, or follow instructions on the court. For that last one, he liked to say, “if I put your brain in a bird, it would fly backwards.” “The kids respected (that),” said Moore. “At the time, coaching in Detroit, where a lot of kids come from not an ideal situation, they needed that tough love. We wanted them to be successful in life.” And while Jones would always say it was about the kids, and Moore would say the same, what they gave each other was almost a half-century-long brotherhood. “We used to get lunch all the time to talk about the kids and how we could be better,” said Moore. “Or we’d grab a beer and talk strategy.” Even in retirement, they talked frequently. So when they talked a couple of weeks back, Moore knew enough to know that his friend sounded fine. Like always. Until he wasn’t. Almost overnight. “I’ve been crying for two days,” said Moore. He is not alone. Not in his grief. Not in his yearning to gather to give his “brother” a proper sendoff. Contact Shawn Windsor: 313-222-6487 or swindsor@freepress.com. Follow him on Twitter @shawnwindsor.

© 2024, Copyrights gulftimes.com. All Rights Reserved