Monday is the national holiday honoring Martin Luther King Jr., who would have turned 90 on Jan. 15. Though he may have been the greatest orator of the 20th century, to remember King only for his powerful words is to underrate him.

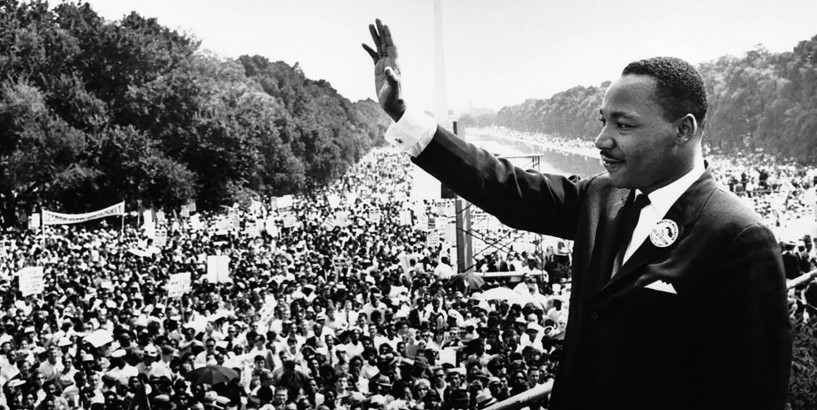

The civil rights leader is best known for his powerful “I have a dream” speech, delivered at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington in 1963. It was the culmination of a march that drew 250,000 demonstrators.

The following year, President Lyndon Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act, prohibiting discrimination in public places and providing for the integration of schools. That same year, King was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

King’s inspiring words and powerful delivery, honed by years of preaching in church pulpits, seemed able to move mountains. But he was also a man of action, fearlessly leading marches in the segregated South, standing up for the rights of black people through nonviolent resistance, even when it landed him in jail, a frequent occurrence.

Without King’s activism, he would be remembered as just another talented public speaker. In 1965, King launched a campaign in Selma, Ala., trying to pressure Congress to pass legislation codifying the rights of black people to vote. Civil rights activists joined with him on a march from Selma to Montgomery on March 7, 1965, and were brutally attacked on what came to be known as Bloody Sunday. President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law five months later.

When sanitation workers in Memphis went on strike for better working conditions in 1968, King travel there and marched with them. It was there, on a Memphis hotel balcony, where bullets fired by James Earl Ray struck and killed King on April 4.

After winning the Nobel in ’64, the civil rights leader could have sat back and written books or given paid speeches, but instead he kept hard at work.

The historian Taylor Branch has written: “In the end, King was not in the company of white presidents or black elites, but marching with the garbagemen of Memphis.”

The late Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New York played a dramatic role in the passage of the bill to make Martin Luther King Day a national holiday.

In October 1983, the U.S. Senate was debating the bill, already passed by the House, where it was co-authored by Republican Rep. Jack Kemp of Erie County.

Sen. Jesse Helms of North Carolina declared his intention to filibuster. Helms claimed the slain civil rights leader was a tool of Marxists. When it neared time for a Senate vote, Helms produced a binder of documents he said demonstrated King’s ties to Communists.

Moynihan held up Helms’ binder and flung it to the ground, pronouncing it “a packet of filth.” The Senate passed the bill by a vote of 78-22, and President Ronald Reagan signed it into law, 15 years after the bill was first proposed in Congress.

It was up to each state to adopt the holiday locally, and several put up resistance. New Hampshire was the last holdout, celebrating its first Martin Luther King Day in 2000.

King might have been disappointed, but probably not surprised, that it took so long for a day honoring him to become the law of the land. He also would have been heartened by the nonviolent activism taking place these days across America.

On Friday, anti-abortion activists held the March for Life on the Mall in Washington, D.C. On Saturday, a Women’s March was held in Washington. Although Buffalo's march was canceled due to the weather, local organizers said the goal was “to increase equity and equality for women and all oppressed people.”

Taking action for oppressed people was what King lived – and gave his life – for. In a 1967 speech denouncing the Vietnam War, King said, “I agree with Dante, that the hottest places in hell are reserved for those who, in a time of moral crisis, maintain their neutrality.”

King made enemies along the way, including jealous rivals, but no one could ever accuse him of staying neutral. His personal courage is what made King a martyr to the civil rights cause, one whose legacy is worth celebrating.