Ninoy had been in detention for eleven months without having any charges filed against him in all that time. It was only eleven months after his arrest in September 1972 that he was brought to face the military court and charges of subversion and illegal possession of firearms were filed against him. An additional charge of murder was also eventually brought against him.

In those first eleven months, we were aware that a number of our close associates and the people who worked for Ninoy had also been arrested and detained.

One of our drivers, in fact, was first to be arrested and detained. He had a photograph of Ninoy and the military authorities ordered him to eat it. They told him, “ Ayan ’yung amo mo; kainin mo ’yung letrato .” His wife, one of the yayas of my children who later on served as my cook, was also picked up and detained. She was three months pregnant then, and was threatened that if she did not cooperate she would be kept in Crame until after she gave birth to her child. They questioned her about Ninoy’s visitors to the house, asking her what they talked about. In reply, she said that there were so many people who came to visit and that, since she was only a maid, she never sat down at any of the conversations. (It made us wonder who these people questioning them were.)

Our other driver actually suffered worse. They beat him up so badly. They placed a briefcase on the side of his head and jumped on it so that his hearing was permanently impaired.

The military had arrested so many people. Even Ninoy’s official photographer was arrested! When he discovered the extent of these arrests, Ninoy instructed me to tell these people to go ahead and confess whatever it was they were being forced to confess, to sign whatever statement they were being forced to sign. He felt it unfair that innocent people be made to suffer alongside him. In any case, Ninoy believed it was a “kangaroo” court, anyway, so there was nothing to it.

It was not enough that they had jailed Ninoy. They also made sure that they had many witnesses to testify against him. The situation posed a dilemma for many, and it was especially difficult for those people who worked with Ninoy, who felt that they were being disloyal to him. But Ninoy told me to assure them that, knowing the circumstances, he would understand. Until I told them it was all right to sign those so-called confessions, they probably would still have held out and waited. There were some, of course, who needed no urging to sign, who did so willingly, and who proved to be such disappointments in this way.

The military captured some of the leading members of the New People’s Army (NPA) as well. These were the people the military used to testify against Ninoy. Commander Melody became a state witness, and Ninoy pointed out that, under normal times, the state witness is also a co-accused, but one who is least guilty. In the case of Commander Melody, he had confessed to killing many members of the PC and many civilians alike.

Afterwards, these people were eliminated. Commander Melody was gunned down in Nepo Mart, in Angeles, Pampanga. Another member of the NPA also died under very mysterious circumstances. The Marcos dictatorship wanted to impute that these witnesses were killed on orders of Ninoy. It seemed like every imaginable crime was being imputed to Ninoy.

Ninoy, at first, was willing to participate in the trial, but the murder charge only came later. Ninoy then felt that these people were just wanting to demolish him, and ridicule him, and make him a non-entity insofar as the Filipinos were concerned. Ninoy’s argument was also that, being a civilian, he should be brought before a civil court. At that time, the civil courts were still operating. Martial law had not abolished them.

He spoke with his lawyers, Senator Tañada and Jovy. Senator Tañada told Ninoy that, if he did not recognize the jurisdiction of the military commission over him, then all he had to do was announce his intent that he would not participate. Jovy, on the other hand, thought that Ninoy should participate in the trial. He told me that, even if Marcos had everything under his control and the military commission was simply going to obey him and follow his directions to the letter, why not buy time. If Ninoy participated, it would give the defense a chance to bring on their own witnesses and to cross-examine the prosecution’s witnesses as well. His point was that, by participating, we could buy time, that as the trial dragged on we might see the end of martial law and Ninoy could have his day in court.

Senator Tañada and Jovy explained to me what I should expect during the trial. Senator Tañada said that the fact that Ninoy would not participate and would announce that he did not recognize the authority of the military court over him, a civilian, in all likelihood the prosecution would merely enumerate the charges against him and not even bother to bring on any witnesses, since Ninoy was not going to refute them anyway. Senator Tañada also warned me to prepare for the possibility that, on the first day of the trial, it could all be over, that Ninoy could right there and then be sentenced to death by firing squad. The charges against Ninoy were of crimes that entailed the heaviest penalty.

The first military commission trial was set for August 1973. For this first trial, I asked the family pediatrician to prescribe some medication for the children to calm them, just a mild dose, because I was sure they were going to be crying. I forget now what she prescribed, but whatever it was had the opposite effect on my second daughter Pinky. She was crying uncontrollably from beginning to end and, afterwards, lost both her contact lenses without her even realizing it! At a certain point, Pinky was talking to Kris and Kris told her, “Pinky, baka pukpukin ang ulo natin ng general.” (The general might hit us on the head.) Gen. Jose Syjuco had been banging away with his gavel and had said that he would send out anyone he caught talking or laughing or smiling.

I remember these humorous incidents now, but it was then a very grave situation.

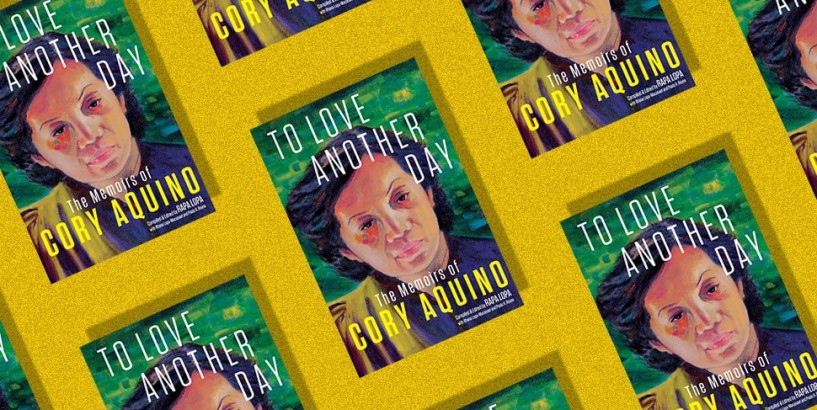

To Love Another Day is available at the Ninoy and Cory Aquino Foundation office. JCS Building, 119 Dela Rosa Street, Legazpi Village, Makati. 02.8812.0403; [email protected]

About the Writer:

Corazon Cojuangco Aquino was the 11th President of the Philippines, the first woman to hold that office. Her husband, Benigno Aquino Jr., an opposition politician, was jailed by President Ferdinand Marcos from 1972 to 1980. He was assassinated in 1983. When Marcos called for snap elections in 1986, Cojuangco Aquino became the candidate of the unified opposition. She was sworn in as President on February 25, 1986.

About the Editor:

Rafael “Rapa” C. Lopa is the president and executive director of the Ninoy and Cory Aquino Foundation, Inc. and a senior advisor to the Office of the Vice President of the Philippines. He is the nephew of the late President Corazon Cojuangco Aquino and served as her executive assistant for seventeen years, from 1993 when she stepped down from office until her death in 2009. Together, they worked on a range of advocacies for social development, human rights, and political and governance reform.