The National Security Law which was imposed on Hong Kong on 1 July violates Hong Kong law, the Chinese constitution, and at least two UN treaties.

It is a fatal blow for the rule of law – so much so that even chambers of commerce are getting concerned , and institutional investors are re-considering risk .

Even for those companies and ministries for whom rose-coloured glasses are standard issue, hope for a trade agreement with China is dwindling in the face of political outrage at China's bullish behaviour.

In a parallel universe, China's lawyers – who should be the guarantors of the rule of law and the checks on Beijing's power – would have been essential to getting bilateral cooperation back on track and securing key preconditions, like legal certainty.

In this universe, sadly, the legal profession in China has had a tough go of it. For the five years since a widespread crackdown began on 9 July 2015, the only 'legal certainty' most of them know is repression.

Lawyer Yu Wensheng circulated a letter calling for constitutional reform online.

Gao Zhisheng defended others for their faith. Wang Yu wanted to protect schoolchildren from sexual abuse.

Li Yuhan wanted to help victims to use China's own laws to get access to information. Instead of being praised, they have been imprisoned.

Authorities have accused these lawyers of undermining national security, subverting the state, or "picking quarrels and provoking troubles".

They have harassed, detained, and disappeared lawyers and other activists – and meanwhile, chased their families out of their homes and kept their children out of school.

Recently, they have adopted more subtle tactics of repression: according to judicial regulations on lawyers and law firms adopted between 2016 and 2018, online speech, questions in court, and even being part of 'sensitive' online chat groups can result in revocation of a lawyer's license to practice, permanent disbarment, or worse.

What has happened in Hong Kong over the past month will make this repression even more severe.

Advocates in Hong Kong who could protest in favour of human rights lawyers – as they did following the so-called '709 crackdown' [7 July] in 2015 – are now facing their own risks. The noose is tightening and critical voices are being silenced.

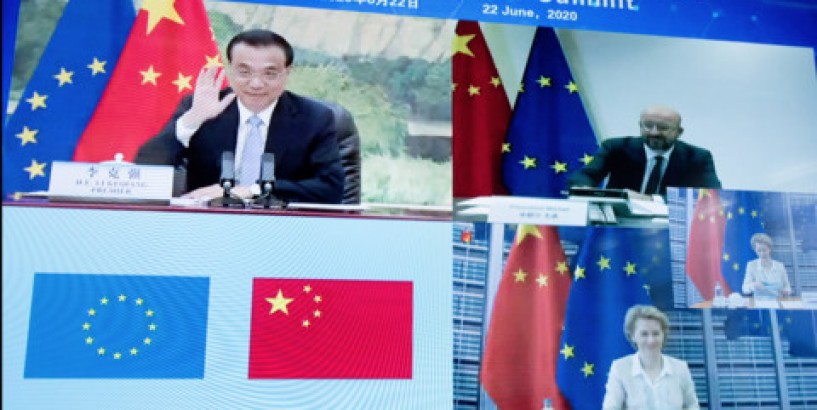

Happening in Europe, too In a feature article on 22 June , an EUobserver reporter noted that Chinese authorities harass EU citizens, residents and their families – within EU borders.

Those helping to support journalists and publishers, or to monitor Chinese companies. Those defending the rights of Uyghurs to practice their religion, speak their language, and reunite with their loved ones.

One need no further proof than the efforts by Chinese diplomatic missions to control the narrative. The day following the feature story on harassment of Uyghurs, EUobserver published a 'right of reply' by the Chinese mission in Brussels whose overwrought and aggressive language reinforces the very arguments it is meant to confront.

Uyghur activists, like lawyers in China and pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong, these defenders are explicitly undermined by a Chinese Communist Party intent on gaslighting them at every opportunity.

So if human rights lawyers are the linchpin for structural change in China – changes that create a positive and reinforcing effect on Europe's interests and values – what should Europe's leadership do?

In one 'high-level dialogue' with China after another, EU leadership has opted for silence over strength.

The EU institutions and member states should strengthen their resolve to use the tools they have – such as export licenses, trade delegations and a targeted sanctions regime – to change the laws that target lawyers, and to see those who have been imprisoned, released.

The EU Commission has committed to multilateralism, but rarely clarifies what that really means.

Relying on 'European values' is not enough, when universal values are at stake. Strategic multilateral diplomacy, with European leadership, can make possible the establishment of a UN envoy to monitor China's rights abuses, including ongoing attacks on China's legal profession.

European states should hold each other accountable while voting at this year's General Assembly in New York. A China so emboldened to violate rights should not get elected to a Human Rights Council tasked with protecting them.

Finally, the EU and its members must continue to stand with the victims of China's violations and those who help them seek justice.

This means doubling down on the EU Guidelines on Human Rights Defenders , and ensuring that EU-China dialogues, rather than being ineffective talk shops, are reimagined to give voice to those most affected by Chinese policies.

Upon accepting the 2019 Franco-German Human Rights Prize , Li Wenzu expressed how encouraging this prize, and the attention of European diplomats in Beijing, was to her and to the families of other lawyers targeted by the so-called '709 crackdown'.

In a speech accepting last year's Sakharov Prize on behalf of her father, Uyghur scholar Ilham Tohti, Jewher Ilham was more direct: 'If you see a problem, please work towards a solution.'

And do it fast, because China's lawyers – and global rule of law – can't wait.

Author bio Sarah M Brooks is Asia advocate at the International Service for Human Rights (ISHR), an NGO based in Switzerland dedicated to supporting and empowering human rights defenders and their communities. Judith Lichtenberg is a member of the board of Lawyers for Lawyers , an independent, non-profit lawyers' organisation based in the Netherlands committed to upholding a free and independent legal profession worldwide.

Disclaimer The views expressed in this opinion piece are the author's, not those of EUobserver.

Opinion